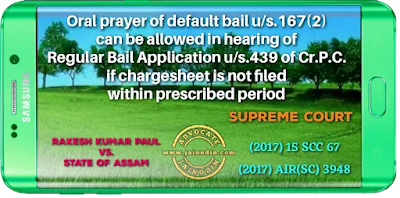

In the present case, it was also argued by learned counsel for the State that the petitioner did not apply for ‘default bail’ on or after 4th January, 2017 till 24th January, 2017 on which date his indefeasible right got extinguished on the filing of the charge sheet. Strictly speaking this is correct since the petitioner applied for regular bail on 11th January, 2017 in the Gauhati High Court – he made no specific application for grant of ‘default bail’. However, the application for regular bail filed by the accused on 11th January, 2017 did advert to the statutory period for filing a charge sheet having expired and that perhaps no charge sheet had in fact being filed. In any event, this issue was argued by learned counsel for the petitioner in the High Court and it was considered but not accepted by the High Court. The High Court did not reject the submission on the ground of maintainability but on merits. Therefore it is not as if the petitioner did not make any application for default bail – such an application was definitely made (if not in writing) then at least orally before the High Court. In our opinion, in matters of personal liberty, we cannot and should not be too technical and must lean in favour of personal liberty. Consequently, whether the accused makes a written application for ‘default bail’ or an oral application for ‘default bail’ is of no consequence. The concerned court must deal with such an application by considering the statutory requirements namely, whether the statutory period for filing a charge sheet or challan has expired, whether the charge sheet or challan has been filed and whether the accused is prepared to and does furnish bail. [Para No.40]

We take this view keeping in mind that in matters of personal liberty and Article 21 of the Constitution, it is not always advisable to be formalistic or technical. The history of the personal liberty jurisprudence of this Court and other constitutional courts includes petitions for a writ of habeas corpus and for other writs being entertained even on the basis of a letter addressed to the Chief Justice or the Court.[Para No.41]

Strong words indeed. That being so we are of the clear opinion that adapting this principle, it would equally be the duty and responsibility of a court on coming to know that the accused person before it is entitled to ‘default bail’, to at least apprise him or her of the indefeasible right. A contrary view would diminish the respect for personal liberty, on which so much emphasis has been laid by this Court as is evidenced by the decisions mentioned above, and also adverted to in Nirala Yadav.[Para No.44]

On 11th January, 2017 when the High Court dismissed the application for bail filed by the petitioner, he had an indefeasible right to the grant of ‘default bail’ since the statutory period of 60 days for filing a charge sheet had expired, no charge sheet or challan had been filed against him (it was filed only on 24 th January, 2017) and the petitioner had orally applied for ‘default bail’. Under these circumstances, the only course open to the High Court on 11 th January, 2017 was to enquire from the petitioner whether he was prepared to furnish bail and if so then to grant him ‘default bail’ on reasonable conditions. Unfortunately, this was completely overlooked by the High Court.[Para No.45]

It was submitted that as of today, a charge sheet having been filed against the petitioner, he is not entitled to ‘default bail’ but must apply for regular bail – the ‘default bail’ chapter being now closed. We cannot agree for the simple reason that we are concerned with

Supreme Court of India

Rakesh Kumar Paul

Vs.

State of Assam

(2017) 15 SCC 67

(2017) AIR(SC) 3948