27 October 2020

Bail can not be denied to chargesheeted accused on the ground of abscondence of other accused

26 October 2020

Mere existence of motive to commit an offence by itself cannot give rise to an inference of guilt nor can it form the basis for conviction

24 October 2020

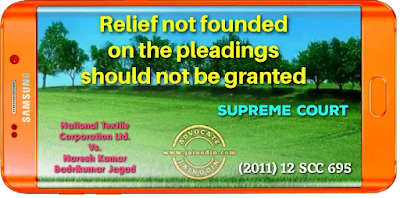

Relief not founded on the pleadings should not be granted

22 October 2020

There is no limitation of period for invoking High Court's inherent powers u/s.482 Cr.P.C.

If evidence is relevant, it is admissible irrespective of how it is obtained

The Investigating Agency has no power to appreciate the evidence

18 October 2020

The proof of demand is an indispensable essentiality to prove the offence under The Prevention of Corruption Act

17 October 2020

Bail should be granted or refused based on the probability of attendance of the party to take his trial

By now it is well settled that

gravity alone cannot be a decisive ground to deny bail, rather competing factors are required to be balanced by the court while exercising its discretion. It has been repeatedly held by the Hon'ble Apex Court thatobject of bail is to secure the appearance of the accused person at his trial by reasonable amount of bail. The object of bail is neither punitive nor preventative. The Hon'ble Apex Court in Sanjay Chandra versus Central Bureau of Investigation (2012)1 Supreme Court Cases 49; has been held as under: "The object of bail is to secure the appearance of the accused person at his trial by reasonable amount of bail.The object of bail is neither punitive nor preventative. Deprivation of liberty must be considered a punishment, unless it can be required to ensure that an accused person will stand his trial when called upon.The Courts owe more than verbal respect to the principle that punishment begins after conviction, and that every man is deemed to be innocent until duly tried and duly found guilty. Detention in custody pending completion of trial could be a cause of great hardship. From time to time, necessity demands that some unconvicted persons should be held in custody pending trial to secure their attendance at the trial but in such cases, "necessity" is the operative test. In India , it would be quite contrary to the concept of personal liberty enshrined in the Constitution that any person should be punished in respect of any matter, upon which, he has not been convicted or that in any circumstances, he should be deprived of his liberty upon only the belief that he will tamper with the witnesses if left at liberty, save in the most extraordinary circumstances. Apart from the question of prevention being the object of refusal of bail,one must not lose sight of the fact that any imprisonment before conviction has a substantial punitive content and it would be improper for any court to refuse bail as a mark of disapproval of former conduct whether the accused has been convicted for it or not or to refuse bail to an unconvicted person for the propose of giving him a taste of imprisonment as a lesson." [Para No.5]

Needless to say

16 October 2020

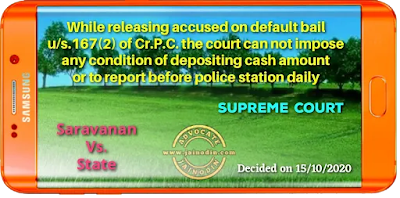

While releasing accused on default bail u/s.167(2) of Cr.P.C. the court can not impose any condition of depositing cash amount or to report before police station daily

15 October 2020

Residence Order passed under The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act does not impose any embargo for filing or continuing civil suit seeking permanent injuction against daughter-in-law

14 October 2020

Mere recovery of blood stained weapon cannot be construed as proof for the murder

For proving the contents of memorandum prepared u/s.27 of Evidence Act, the Investigating Officer must state the exact narration of facts in such document in his own words while deposing before the Court

17. Now as regards the proving of such information, the matter seems to us to be governed by Sections 60, 159 and 160 of the Evidence Act. It is correct thatstatements and reports prepared outside the court cannot by themselves be accepted as primary or substantive evidence of the facts stated therein. Section 60 of the Evidence Act lays down that oral evidence must, in all cases whatever, be direct, that is to say, if it refers to a fact which could be seen, it must be the evidence of a witness who says he saw it, and if it refers to a fact which could be heard, it must be the evidence of a witness who says he heard it and so on. Section 159 then permits a witness while under examination to refresh his memory by referring to any writing made by himself at the time of the transaction concerning which he is questioned, or so soon afterwards that the court considers it likely that the transaction was at that time fresh in the memory. Again, with the permission of the court, the witness may refresh, his memory by referring to a copy of such document. And the witness may even refer to any such writing made by any other person but which was read by him at the time the transaction was fresh in his memory and when he read it, he knew it to be correct. Section 160 then provides for cases where the witness has no independent recollection say, from lapse of memory, of the transaction to which he wants to testify by looking at the document and states that although he has no such recollection he is sure that the contents of the document were correctly recorded at the time they were. It seems to us that where a case of this character arises and the document itself has been tendered in evidence, the document becomes primary evidence in the case. See Jagan Nath v. Emperor, AIR 1932 Lah 7.The fundamental distinction between the two sections is that while under Section 159 it is the witness's memory or recollection which is evidence, the document itself not having been tendered in evidence; under Section 160, it is the document which is evidence of the facts contained in it. It has been further held that in order to bring a case under Section 160, though the witness should ordinarily affirm on oath that he does not recollect the facts mentioned in the document, the mere omission to say so will not make the document inadmissible provided the witness swears that he is sure that the facts are correctly recorded in the document itself. Thus in Partab Singh v. Emperor, AIR 1926 Lah 310 it was held that where the surrounding circumstances intervening between the recording of a statement and the trial would as a matter of normal human experience render it impossible for a police officer to recollect and reproduce the words used, his statement should be treated as if he had prefaced it by stating categorically that he could not remember what the deceased in that case had said to him. Putting the whole thing in somewhat different language, what was held was that Section 160 of the Act applies equally when the witness states in so many words that he has no independent recollection of the precise words used, or when it should stand established beyond doubt that that should be so as a matter of natural and necessary conclusion from the surrounding circumstances.18. Again, in Krishnama v. Emperor, AIR 1931 Mad 430 a Sub-Assistant Surgeon recorded the statement made by the deceased just before his death, which took place in April, 1930, and the former was called upon to give evidence some time in July, 1930. In the Sessions Court he just put in the recorded statement of the deceased which was admitted in evidence. On appeal it was objected that such statement was wrongly admitted inasmuch as the witness did not use it to refresh his memory nor did he attempt from recollection to reproduce the words used by the accused. It was held that he could not have been expected to reproduce the words of the deceased, and therefore, he was entitled to put in the document as a correct record of what the deponent had said at the time on the theory that the statement should be treated as if the witness had prefaced it by stating categorically that he could not remember what the deceased had said.19. Again in Public Prosecutor v. Venkatarama Naidu, AIR 1943 Mad 542, the question arose how the notes of a speech taken by a police officer be admitted in evidence. It was held that it was not necessary that the officer should be made to testify orally after referring to those notes. The police officer should describe his attendance, the making of the relevant speech and give a description of its nature so as to identify his presence there and his attention to what was going on, and that after that it was quite enough it he said "I wrote down that speech and this is what I took down," and if the prosecution had done that, they would be considered to have proved the words. This case refers to a decision of the Lahore High Court in Om Prakash v. Emperor, AIR 1930 Lah 867 wherein the contention was raised that the notes of a speech taken by a police officer were not admissible in evidence as he did not testify orally as to the speech and had not refreshed his memory under Section 159 of the Evidence Act from those notes. It was held that instead of deposing orally as to the speech made by the appellant, the police officer had put in the notes made by him, and that there would be no difference between this procedure and the police officer deposing orally after reference to those notes, and that for all practical purposes, that would be one and the same thing.20. The same view appears to us to have been taken in Emperor v. Balaram Das, AIR 1922 Cal 382 (2).21. From the discussion that we have made, we think that the correct legal position is somewhat like this.Normally, a police officer (or a Motbir) should reproduce the contents, of the statement made by the accused under Section 27 of the Evidence Act in Court by refreshing his memory under Section 159 of the Evidence Act from the memo earlier prepared thereof by him at the time the statement had been made to him or in his presence and which was recorded at the same time or soon after the making of it and that would be a perfectly unexceptionable way of proving such a statement. We do not think in this connection, however, that it would be correct to say that he can refer to the memo under Section 159 of the Evidence Act only if he establishes a case of lack of recollection and not otherwise. We further think that where the police officer swears that he does not remember the exact words used by the accused from lapse of time or a like cause or even where he does not positively say so but it is reasonably established from the surrounding circumstances (chief of which would be the intervening time between the making of the statement and the recording of the witness's deposition at the trial) that it could hardly be expected in the natural course of human conduct that he could or would have a precise or dependable recollection of the same, then under Section 160 of the Evidence Act, it would be open to the witness to rely on the document itself and swear that the contents thereof are correct where he is sure that they are so and such a case would naturally arise where he happens to have recorded the statement himself or where it has been recorded by some one else but in his own presence, and in such a case the document itself would be acceptable substantive evidence of the facts contained therein. With respect, we should further make it clear that in so far as Chhangani, J.'s holds to the contrary, we are unable to accept it as laying down the correct law. We hold accordingly."

Rejection of a bail application by Sessions Court does not operate as a bar for the High Court in entertaining a similar application under Section 439 Cr. P. C.

In the instant case, learned Principal Sessions Judge, Samba, has rejected the bail petition of both the petitioners. The question that arises for consideration is whether or not successive bail applications will lie before this Court. The law on this issue is very clear that

"It is significant to note that under Section 397, Cr.P.C of the new Code while the High Court and the Sessions Judge have the concurrent powers of revision, it is expressly provided under sub-section (3) of that section that when an application under that section has been made by any person to the High Court or to the Sessions Judge, no further application by the same person shall be entertained by the other of them. This is the position explicitly made clear under the new Code with regard to revision when the authorities have concurrent powers. Similar was the position under Section 435(4), Cr.P.C of the old Code with regard to concurrent revision powers of the Sessions Judge and the District Magistrate. Although, under Section 435(1) Cr.P.C of the old Code the High Court, a Sessions Judge or a District Magistrate had concurrent powers of revision, the High Court's jurisdiction in revision was left untouched. There is no provision in the new Code excluding the jurisdiction of the High Court in dealing with an application under Section 439(2), Cr.P.C to cancel bail after the Sessions Judge had been moved and an order had been passed by him granting bail. The High Court has undoubtedly jurisdiction to entertain the application under Section 439(2), Cr.P.C for cancellation of bail notwithstanding that the Sessions Judge had earlier admitted the appellants to bail. There is, therefore, no force in the submission of Mr Mukherjee to the contrary."[Para No.5]

"The above view of the learned Single Judge of the Kerala High Court appears to me to be correct. In fact, it is now well-settled that

there is no bar whatsoever for a party to approach either the High Court or the Sessions Court with an application for an ordinary bail made under Section 439 Cr.P.C. The power given by Section 439 to the High Court or to the Sessions Court is an independent power and thus, when the High Court acts in the exercise of such power it does not exercise any revisional jurisdiction, but its original special jurisdiction to grant bail. This being so, it becomes obvious that although under section 439 Cr.P.C. concurrent jurisdiction is given to the High Court and Sessions Court,the fact, that the Sessions Court has refused a bail under Section 439 does not operate as a bar for the High Court entertaining a similar application under Section 439 on the same facts and for the same offence. However,if the choice was made by the party to move first the High Court and the High Court has dismissed the application, then the decorum and the hierarchy of the Courts require that if the Sessions Court is moved with a similar application on the same fact, the said application be dismissed. This can be inferred also from the decision of the Supreme Court in Gurcharan Singh's case (above)."[Para No.6]

13 October 2020

While deciding an application for rejection of plaint under Order VII Rule 11 CPC, the court is required to take the averments made therein to be correct

"10. Clause (d) of Order 7 Rule 11 speaks of suit, as appears from the statement in the plaint to be barred by any law.Disputed questions cannot be decided at the time of considering an application filed under Order 7 Rule 11 CPC. Clause (d) of Rule 11 of Order 7 applies in those cases only where the statement made by the plaintiff in the plaint, without any doubt or dispute shows that the suit is barred by any law in force.19. There cannot be any compartmentalisation, dissection, segregation and inversions of the language of various paragraphs in the plaint. If such a course is adopted it would run counter to the cardinal canon of interpretation according to which a pleading has to be read as a whole to ascertain its true import. It is not permissible to cull out a sentence or a passage and to read it out of the context in isolation. Although it is the substance and not merely the form that has to be looked into, the pleading has to be construed as it stands without addition or subtraction of words or change of its apparent grammatical sense. The intention of the party concerned is to be gathered primarily from the tenor and terms of his pleadings taken as a whole. At the same time it should be borne in mind that no pedantic approach should be adopted to defeat justice on hair-splitting technicalities." (emphasis added)[Para No.16]

10 October 2020

Mere registration of FIR regarding ragging of a student is not the ground for suspending the accused-student from educational institute

Before suspending accused-student, the educational institute must get satisfied itself about the truth of allegations of ragging

09 October 2020

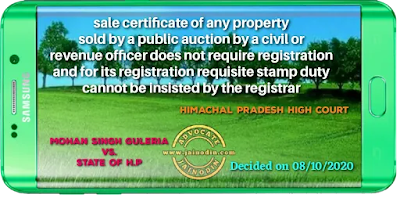

sale certificate of any property sold by a public auction by a civil or revenue officer does not require registration and for its registration requisite stamp duty cannot be insisted by the registrar

"24. Learned Senior Counsel appearing on behalf of the writ petitioner argued that the authorities concerned have refused to register the sale and make the entries in the revenue records on the ground that the necessary permission was to be obtained as per the mandate of Section 118 of the Act.25. It is also contended that the sale certificate and the confirmation of sale issued by the authorities, i.e. Annexures P6 and P8, are necessary to be registered before the authority concerned in terms of the mandate of Section 17 of the Registration Act, 1908 (for short "the Registration Act"), which is not legally correct.

26.Section 17 of the Registration Act, though mandatory in nature, provides which of the documents are compulsory to be registered. It does not include sale by auction and sale certificate issued by the concerned authorities including confirmation of sale, which are outcome of the auction proceedings conducted in terms of Court orders. The provision is speaking one and without any ambiguity.Thus, registration was not required. The Apex Court in the case titled as B. Arvind Kumar versus Govt. of India and others, 2007 5 SCC 745 , held thata sale certificate issued by a Court or an officer authorized by the Court does not require registration. It is apt to reproduce para 12 of the judgment herein:

"12. The plaintiff has produced the original registered sale certificate dated 29.8.1941 executed by the Official Receiver, Civil Station, Bangalore. The said deed certifies that Bhowrilal (father of plaintiff) was the highest bidder at an auction sale held on 22.8.1941, in respect of the right, title, interest of the insolvent Anraj Sankla, namely the leasehold right in the property described in the schedule to the certificate (suit property), that his bid of Rs. 8,350.00 was accepted and the sale was confirmed by the District Judge, Civil and Military Station, Bangalore on 25.8.1941. The sale certificate declared Bhowrilal to be the owner of the leasehold right in respect of the suit property. When a property is sold by public auction in pursuance of an order of the court and the bid is accepted and the sale is confirmed by the court in favour of the purchaser, the sale becomes absolute and the title vests in the purchaser. A sale certificate is issued to the purchaser only when the sale becomes absolute. The sale certificate is merely the evidence of such title. It is well settled thatwhen an auction purchaser derives title on confirmation of sale in his favour, and a sale certificate is issued evidencing such sale and title, no further deed of transfer from the court is contemplated or required. In this case,the sale certificate itself was registered, though such a sale certificate issued by a court or an officer authorized by the court, does not require registration. Section 17(2)(xii) of the Registration Act, 1908 specifically provides thata certificate of sale granted to any purchaser of any property sold by a public auction by a civil or revenue officer does not fall under the category of non testamentary documents which require registration under subsec. (b) and (c) of sec. 17(1) of the said Act. We therefore hold that the High Court committed a serious error in holding that the sale certificate did not convey any right, title or interest to plaintiff's father for want of a registered deed of transfer."

28. The same principle has been laid down by the Apex Court in the case titled as Som Dev and others versus Rati Ram and another, 2006 10 SCC 788 . It would be profitable to reproduce para 15 of the judgment herein:

"15. Almost the whole of the argument on behalf of the appellants here, is based on the ratio of the decision of this Court in Bhoop Singh v. Ram Singh Major, 1995 5 SCC 709 , It was held in that case that exception under clause (vi) of Section 17(2) of the Act is meant to cover that decree or order of a Court including the decree or order expressed to be made on a compromise which declares the preexisting right and does not by itself create new right, title or interest in praesent in immovable property of the value of Rs.100/ or upwards. Any other view would find the mischief of avoidance of registration which requires payment of stamp duty embedded in the decree or order. It would, therefore, be the duty of the Court to examine in each case whether the parties had preexisting right to the immovable property or whether under the order or decree of the Court one party having right, title or interest therein agreed or suffered to extinguish the same and created a right in praesenti in immovable property of the value of Rs.100/ or upwards in favour of the other party for the first time either by compromise or pretended consent. If latter be the position, the document is compulsorily registrable. Their Lordships referred to the decisions of this Court in regard to the family arrangements and whether such family arrangements require to be compulsorily registered and also the decision relating to an award. With respect, we may point out that an award does not come within the exception contained in clause (vi) of Section 17(2) of the Registration act and the exception therein is confined to decrees or orders of a Court. Understood in the context of the decision in Hemanta Kumari Debi v. Midnapur Zamindari Co. Ltd., 1919 AIR(PC) 79 and the subsequent amendment brought about in the provision, the position that emerges is thata decree or order of a court is exempted from registration even if clauses (b)and (c) of Section 17(1) of the Registration Act are attracted, and even a compromise decree comes under the exception, unless, of course, it takes in any immovable property that is not the subject matter of the suit.

29. A question arose before the Madras High Court in a case titled as K. Chidambara Manickam versus Shakeena & Ors., 2008 AIR(Mad) 108 , whether the sale of secured assets in public auction which ended in issuance of a sale certificate is a complete and absolute sale or whether the sale would become final only on the registration of the sale certificate? It has been held that the sale becomes final when it is confirmed in favour of the auction purchaser, he is vested with rights in relation to the property purchased in auction on issuance of the sale certificate and becomes the absolute owner of the property. The sale certificate does not require any registration. It is apt to reproduce paras 10.13, 10.14, 10.17 and 10.18 of the judgment herein:-

"10.13 Part III of the Registration Act speaks of the Registration of documents. Section 17(1) of the Registration Act enumerates the documents which require compulsory Registration. However, subsection (2) of Section 10 sets out the documents to which clause (b) and (c) of subsection (1) of Section 17 do not apply. Clause (xii) of subsection (2) of Section 17 of the Registration Act reads as under:"Section 17(2)(xii) any certificate of sale granted to the purchaser of any property sold by public auction by a Civil or Revenue Officer."

10.14 A Division Bench of this Court in Arumugham, S. v. C.K. Venugopal Chetty,1994 1 LW 491 , held that the property transferred by Official Assignee, under order of Court, does not require registration under Section 17 of the Registration Act. The Division Bench has held as follows:

Court of Sessions can permit u/s. 301, 24(8) of CrPC to the advocate of victim to make oral argument too apart from submission of the written argument

Advocate is treated to be officer of the court and supposed to assist the court in arriving the truth, so, right to address the court to an Advocate cannot be curtailed while representing his client

07 October 2020

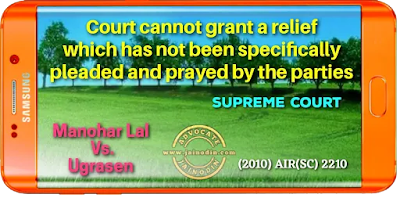

Court cannot grant a relief which has not been specifically pleaded and prayed by the parties

"It is well settled thatthe decision of a case cannot be based on grounds outside the pleadings of the parties and it is the case pleaded that has to be found. Without an amendment of the plaint, the Court was not entitled to grant the relief not asked for and no prayer was ever made to amend the plaint so as to incorporate in it an alternative case."[Para No.29]

"Though the Court has very wide discretion in granting relief, the court, however, cannot, ignoring and keeping aside the norms and principles governing grant of relief, grant a relief not even prayed for by the petitioner."[Para No.31]

Temporary appointment in a service can not be regularised as permanent service

"15. Even at the threshold, it is necessary to keep in mind the distinction between regularization and conferment of permanence in service jurisprudent. In State of Mysore v. S.V. Narayanappa [(1976) 1 SCR 128: AIR 1967 SC 1071] this Court stated that it was a misconception to consider that regularization meant permanence. In R.N. Nanjundappa v. T. Thimmiah [(1972) 1 SCC 409: (1972) 2 SCR 799] this Court dealt with an argument that regularization would mean conferring the quality of permanence on the appointment. This Court stated: (SCC pp. 416-17, para 26)"Counsel on behalf of the respondent contended that regularization would mean conferring the quality of permanence on the appointment whereas counsel on behalf of the State contended that regularization did not mean permanence but that it was a case of regularization of the rules under Article 309. Both the contentions are fallacious. If the appointment itself is in infraction of the rules or if it is in violation of the provisions of the Constitution illegality cannot be regularized. Ratification or regularization is possible of an act which is within the power and province of the authority but there has been some non-compliance with procedure or manner which does not go to the root of the appointment. Regularization cannot be said to be a mode of recruitment. To accede to such a proposition would be to introduce a new head of appointment in defiance of rules or it may have the effect of setting at naught the rules."16. In B. N. Nagarajan v. State of Karnataka [(1979) 4 SCC 507: 1980 SCC (L&S) 4: (1979) 3 SCR 937] this Court clearly held that the words "regular" or "regularization" do not connote permanence and cannot be construed so as to convey an idea of the nature of tenure of appointments. They are terms calculated to condone any procedural irregularities and are meant to cure only such defects as are attributable to methodology followed in making the appointments. This Court emphasized that when rules framed under Article 309 of the Constitution are in force, no regularization is permissible in exercise of the executive powers of the Government under Article 162 of the Constitution in contravention of rules. These decisions and the principles recognized therein have not been dissented to by this Court and on principle, we see no reason not to accept the proposition as enunciated in the above decisions. We have, therefore, to keep this distinction in mind and proceed on the basis that only something that is irregular for want of compliance with one of the elements in the process of selection which does not go to the root of the process, can be regularized and that it alone can be regularized and granting permanence of employment is a totally different concept and cannot be equated with regularization.53. One aspect needs to be clarified. There may be cases where irregular appointments (not illegal appointments) as explained in S.V. Narayanappa [(1967) 1 SCR 128: AIR 1967 SC 1071], R. N. Nanjundappa [(1972) 1 SCC 409: (1972) 2 SCR 799] and B.N. Nagarajan [(1979) 4 SCC 507: 1980 SCC (L&S) 4: (1979) 3 SCR 937] and referred to in para 15 above, of duly qualified persons in duly sanctioned vacant posts might have been made and the employees have continued to work for ten years or more but without the intervention of orders of the courts or of tribunals. The question of regularization of the services of such employees may have to be considered on merits in the light of the principles settled by this Court in the cases above referred to and in the light of this judgement. In that context, the Union of India, the State Governments and their instrumentalities should take steps to regularize as a one-time measure, the services of such irregularly appointed, who have worked for ten years or more in duly sanctioned posts but not under cover of orders of the courts or of tribunals and should further ensure that regular recruitments are undertaken to fill those vacant sanctioned posts that require to be filled up, in cases where temporary employees or daily wagers are being now employed. The process must be set in motion within six months from this date. We also clarify that regularization, if any already made, but not sub judice, need not be reopened based on this judgement, but there should be no further bypassing of the constitutional requirement and regularizing or making permanent, those not duly appointed as per the constitutional scheme"[Para No.19]

In my considered opinion, the petitioners cannot rely upon the doctrine of legitimate expectation to seek regularization of employment. The petitioners from the very beginning of their contract were fully aware of the temporary nature of employment and that it would expire within stipulated period unless extended by the Government. The Hon'ble Apex Court in this regard has dealt with this principle in Umadevi (Supra) and held as follows:

"47.When a person enters a temporary employment or gets engagements as a contractual or casual worker and the engagement is not based on a proper selection as recognized by the relevant rules or procedure, he is aware of the consequences of the appointment being temporary, casual or contractual in nature. Such a person cannot invoke the theory of legitimate expectation for being confirmed in the post when an appointment to the post could be made only by following a proper procedure for selection and in concerned cases, in consultation with the Public Service Commission. Therefore, the theory of legitimate expectation cannot be successfully advanced by temporary, contractual or casual employees. It cannot also be held that the State has held out any promise while engaging these persons either to continue them where they are or to make them permanent. The State cannot constitutionally make such a promise. It is also obvious that the theory cannot be invoked to seek a positive relief of being made permanent of the post.

06 October 2020

Whenever the process of election starts, normally courts should not interfere with the process of election

"14. In our opinion, the High Court was not right in interfering with the process of election especially when the process of election had started upon publication of the election program on 27th January, 2011 and more particularly when an alternative statutory remedy was available to Respondent no.1 by way of referring the dispute to the Central Government as per the provisions of Section 5 of the Act read with Regulation 20 of the Regulations. So far as the issue with regard to eligibility of Respondent no.1 for contesting the election is concerned, though prima facie it appears that Respondent no.1 could contest the election, we do not propose to go into the said issue because, in our opinion, as per the settled law, the High Court should not have interfered with the election after the process of election had commenced. The judgments referred to hereinabove clearly show the settled position of law to the effect thatwhenever the process of election starts, normally courts should not interfere with the process of election for the simple reason that if the process of election is interfered with by the courts, possibly no election would be completed without court's order. Very often, for frivolous reasons candidates or others approach the courts and by virtue of interim orders passed by courts, the election is delayed or cancelled and in such a case the basic purpose of having election and getting an elected body to run the administration is frustrated. For the aforestated reasons, this Court has taken a view that all disputes with regard to election should be dealt with only after completion of the election.15. This Court, in Ponnuswami v. Returning Officer (supra) has held thatonce the election process starts, it would not be proper for the courts to interfere with the election process. Similar view was taken by this Court in Shri Sant Sadguru Janardan Swami (Moingiri Maharaj) Sahakari Dugdha Utpadak Sanstha v. State of Maharashtra (supra)."[Para No.35]

plaintiff has no absolute right, at the appellate stage, to withdraw from the suit

"No doubt, the grant of leave envisaged in sub-rule (3) of Rule 1 is at the discretion of the court but such discretion is to be exercised by the court with caution and circumspection. ...... The court is to discharge the duty mandated under the provision of the Code on taking into consideration all relevant aspects of the matter including the desirability of permitting the party to start a fresh round of litigation on the same cause of action. This becomes all the more important in a case where the application under Order 23 Rule 1 is filed by the plaintiff at the stage of appeal. Grant of leave in such a case would result in the unsuccessful plaintiff to avoid the decree or decrees against him and seek a fresh adjudication of the controversy on a clean slate. It may also result in the contesting defendant losing the advantage of adjudication of the dispute by the court or courts below. Grant of permission for withdrawal of a suit with leave to file a fresh suit may also result in annulment of a right vested in the defendant or even a third party. The appellate/second appellate court should apply its mind to the case with a view to ensure strict compliance with the conditions prescribed in Order 23 Rule 1(3) C.P.C for exercise of the discretionary power in permitting the withdrawal of the suit with leave to file a fresh suit on the same cause of action.Yet another reason in support of this view is that withdrawal of a suit at the appellate/second appellate stage results in wastage of public time of courts which is of considerable importance in present time in view of large accumulation of cases in lower courts and inordinate delay in disposal of the cases. ........ It is the duty of the court to feel satisfied that there exist proper grounds/reasons for granting permission for withdrawal of the suit with leave to file fresh suit by the plaintiffs and in such a matter the statutory mandate is not complied with by merely stating that grant of permission will not prejudice the defendants.In case such permission is granted at the appellate or second appellate stage prejudice to the defendant is writ large as he loses the benefit of the decision in his favour in the lower court". (emphasis supplied).[Para No.29]

"Since withdrawal of suit at the appellate stage, if allowed, would have the effect of destroying or nullifying the decree affecting thereby rights of the parties which came to be vested under the decree, it cannot be allowed as a matter of course but has to be allowed rarely only when a strong case is made out. .....Where a decree passed by the Trial Court is challenged in appeal, it would not be open to the plaintiff, at that stage, to withdraw the suit as to destroy that decree. The rights which have come to be vested in the parties to the suit under the decree cannot be taken away by withdrawal of the suit at that stage unless very strong reasons are shown that the withdrawal would not affect or prejudice anybody's vested rights". [Para No.30]

04 October 2020

It amounts defamation u/s.499 of IPC if defamatory contents of pleading filed in a matrimonial case are revealed to relatives and friends of complainant

In the case of M.K. Prabhakaran and another Vs.T.E. Gangadharan and another reported in 2006 CRI.L.J. 1872, the Kerala High Court, in a matter where it is alleged that defamatory statements against complainant were made in a written statement filed before the Court held that,

"11. In Sandyal V.Bhaba Sundari Debi 7 Ind.Cas.803:15 C.W.N. 995:14 C.L.J.31 the learned Judges, following the case of Augada Ram Shaha V. Nemai Chand Shaha 23 C.867;12 Ind.Dec.(n.s.)576, held thatdefamatory statements made in the written statement of a party in a judicial proceedings are not absolutely privileged in this country, and that a qualified privilege in this regard cannot be claimed in respect of such statements, unless they fall within the Exceptions to Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code. Undisputedly, the case of the petitioner was not in any of these Exceptions.12. For criminal purposes "publication" has a wider meaning than it has in civil law, since it includes a communication to the person defamed alone.The prosecution for defamation in criminal cases can be brought although the only publication is to the person defamed as it is very likely to provoke a breach between the persons involved...."

02 October 2020

Husband is duty bound to maintain his dependants, regardless of his job and income

“4.Now that the matter is going back to the original Court we think it appropriate to bring it to the notice of the learned Magistrate that under Section 125 of the CrPCeven an illegitimate minor child is entitled to maintenance.

“The other findings of the Magistrate on the disputed question of fact were recorded after a full consideration of the evidence an should have been left undisturbed in revision. No error of law appears to have been discovered in his judgment and so the revisional courts were not justified in making a reassessment of the evidence and substitute their own views for those of the Magistrate. (See Pathumma and another v. Mahammad, [1986] 2 SCC 585). Besides holding that the respondent had married the appellant, the Magistrate categorically said that the appellant and the respondent lived together as husband and wife for a number of years and the appellant No. 2 Maroti was their child. If, as a matter of fact, a marriage although ineffective in the eye of law, took place between the appellant No. 1 and the respondent No. 1, the status of the boy must be held to be of a legitimate son on account of s. 16(1) of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, which reads as follows:

"16(1). Notwithstanding that a marriage is null and void under Section 11, any child of such marriage who would have been legitimate if the marriage had been valid, shall be legitimate, whether such child is born before or after the commencement of the Marriage Laws (Amendment) Act, 1976 (68 of 1976), and whether or not a decree of nullity is granted in respect of that marriage under this Act and whether or not the marriage is held to be void otherwise than on a petition under this Act."

Financier is the real owner of a vehicle, covered by a hire purchase agreement till all the hire instalments are paid

The Consumer Protection Act, 1986 does not override the Contract Act, 1872, and other enactments

"Consumer is a merely a trustee of vehicle under hire-purchase agreement"

“5. Hire-purchase agreements are executory contracts under which the goods are let on hire and the hirer has an option to purchase in accordance with the terms of the agreement. These types of agreements were originally entered into between the dealer and the customer and the dealer used to extend credit to the customer. But as hire- purchase scheme gained in popularity and in size, the dealers who were not endowed with liberal amount of working capital found it difficult to extend the scheme to many customers. Then the financiers came into the picture.The finance company would buy the goods from the dealer and let them to the customer under hire-purchase agreement. The dealer would deliver the goods to the customer who would then drop out of the transaction leaving the finance company to collect instalments directly from the customer. Under hire-purchase agreement, the hirer is simply paying for the use of the goods and for the option to purchase them. The finance charge, representing the difference between the cash price and the hire-purchase price, is not interest but represents a sum which the hirer has to pay for the privilege of being allowed to discharge the purchase price of goods by instalments. 7. In Damodar Valley Corpn. v. State of Bihar AIR 1961 SC 440 this Court took the view that a mere contract of hiring, without more, is a species of the contract of bailment, which does not create a title in the bailee, but the law of hire purchase has undergone considerable development during the last half a century or more and has introduced a number of variations, thus leading to categories and it becomes a question of some nicety as to which category a particular contract between the parties comes under.Ordinarily, a contract of hire purchase confers no title on the hirer, but a mere option to purchase on fulfilment of certain conditions. But a contract of hire purchase may also provide for the agreement to purchase the thing hired by deferred payments subject to the condition that title to the thing shall not pass until all the instalments have been paid. There may be other variations of a contract of hire purchase depending upon the terms agreed between the parties. When rights in third parties have been created by acts of parties or by operation of law, the question may arise as to what exactly were the rights and obligations of the parties to the original contract.[Para no.64]

In Charanjit Singh Chadha (supra), this Court held that